Setting the Boat Up

Many sailors alter the way their boat is set up for sailing in a blow. Listed below are some of the changes that I and other dart fifteeners make for sailing in strong winds.

Batten Tension - Reducing batten tension reduces the curvature of the sail and consequently the power that it produces. As the wind strength increases I reduce my batten tension, starting from the top of the sail and gradually working down. By the time the wind is ~F5+, I have very little batten tension. In my experience this lets me sheet the traveller further in upwind than with tighter battens so the boat points higher and reduces the force on the bows offwind so the bows dig in less often. One word of warning. If you do reduce the batten tension this much, tie plenty of knots. When there is no tension, the battens seem to come undone far more easily and are likely fall over the back at an inopportune moment if there aren't enough knots.

Mast rake - is often changed for sailing in a blow. The theory is that raking the mast back, moves the centre of effort of the sail further back and reduces the tendency of the bows to nose-dive. I haven't found that raking my mast back has had any significant effects in this area. One effect that it does have is that the potential for sheeting the main in is reduced. The result of this is that the mainsheet will be block-to-block before it is fully sheeted in, allowing the top of the sail to fall away. In my experience, this reduces the pointing ability of the boat losing distance to other boats upwind.

Rig tension - As the wind increases I gradually increase my rig tension. In lighter winds it is necessary to reduce rig tension to allow the mast to rotate. As the wind increases, however, rig tension may be increased to stiffen the boat and to stop the mast leaning to leeward losing power and increasing weather helm. The values listed in Paul Smith's article in the last newsletter seem about right to me. A really tight tramp is another key to a stiff boat. Next time your tramp is off the boat, pick up one of the bows and watch how far it has to be lifted before the other lifts. Replace tramp and tie really tight (yes those hanks bend on my boat too..).

On the Water

Before the start - Avoid blasting around aimlessly, gains can be made by investing the time before the start. Sail the boat upwind, get a feel for the correct position of the traveller, where is it in relation to the toestraps/traveller markings? Remember this for the race. Put plenty of downhaul on. This flattens the sail and reduces the heeling moment. To get the downhaul really hard on, sheet the mainsheet in with the traveller out (to avoid capsizing - you will never live that one down), let the boat gradually head up into the wind and pull on a much downhaul as possible, standing on the rope if required. The 3-to-1 downhaul arrangement helps here. Practice tacking and gybing. Can you tack without stalling? Do you remain in full control during the gybes? Bear off onto a run. Will you have to release the downhaul to allow the mast to rotate, or is it too windy to venture that far forward? Try and remove as many variables from the race itself, to allow yourself to concentrate fully on sailing the boat fast and making tactical decisions.

The Start - Start as normal, but take special care to create a gap to leeward of you to avoid getting caught directly to windward of a boat that is being luffed up hard because the traveller is too hard in. This is a guaranteed way to lose fifty yards on the boats sailing flatter with the traveller further out.

Sailing Upwind

Sheet the main in as hard as possible and adjust the traveller to a position where the boat is nicely powered up, without having to constantly luff to spill wind. It is possible to sail upwind with the traveller fully out, as long as the mainsheet is in hard.

Sit hard against the shroud. If this causes the leeward bow to dig into the waves and slow you down, gradually move back until you find a position which minimises the bow digging in without sitting too far back and dragging the sterns. Sit out hard and try to keep the boat as flat as possible. When a gust strikes and the boat becomes overpowered, luffing up will reduce the heel of the boat and gain ground to windward. If the gust is strong, or it took you by surprise, it may be necessary to let out some mainsheet as well. Look upwind every ten seconds for gusts. When you see a gust coming, try and judge how strong it will be. Let the traveller out beforehand if necessary. Just before the gust strikes, sit out hard and head up slightly. If the boat is allowed to heel too much, the righting moment is reduced and the boat will be less powered up, reducing forward speed. The rig leaning to leeward of the centreline will give the boat excessive weather helm, the skegs become less efficient as the boat slows and ground to windward will be lost with the increased leeway.

Keeping the boat flat during the gusts with a combination of sitting out hard, luffing and spilling wind when necessary, will gain you many yards over boats that are sailed with more heel in the gusts.

Tacking - It is easy to stall tacks in strong winds. It is likely that the boat will not be sailing as close to the wind as usual as the traveller is further out. Increased boat heel will reduce the speed of the boat and the waves are larger then normal, all increasing the likelihood of stalling the tack.

Pick a flat stretch of water on which to tack. Sit out hard and keep the boat as flat as possible just before the tack to get up boatspeed. If there are large waves, tack up the face of a wave. Push the tiller away hard to start the tack - it is important to keep the rudders hard over throughout the tack or the boat will lose its momentum. As the boat passes through the eye of the wind, cross the boat, uncleat the mainsheet and let out a foot of sheet. Don't leave the mainsheet cleated in throughout the tack as the risks of capsize are high (Dad knows a thing or two about this.....). Sit out on the new side and pull the sheet in when ready.

If the boat does stall and begin to sail backwards, reverse the rudders and let out a couple of feet of sheet. Bear off more than usual on the new tack to get going before sheeting in and sailing off.

The First Reach

Begin to prepare for the first reach a few yards short of the windward mark. Let the traveller out to the appropriate position, (usually the end of the track), and sit right back to avoid digging a bow in as you bear off around the mark. It helps if you get the rear beam between your legs. This gets the weight right back and stops you sliding forward if a bow digs in and the boat slows quickly.

Aim for the mark and try to sail the shortest course. When a gust strikes or the leeward bow digs in, let out some sheet immediately to reduce the force on the bow and sit out hard. If the leeward bow still digs in luffing up will further reduce the force on the bow and the bow should pop up. Again look over your shoulder every ten seconds to check for gusts so you can be prepared. When sailing on a close reach where the boat has a tendency to heel there are again benefits from keeping the boat as flat as possible

When the boat is not fully powered up offwind, it often pays to head up in the lulls and bear off in the gusts. This way the boat meets the gusts sooner and stays with them longer. In a blow this situation can be reversed where pointing up in the gusts is necessary to avoid burying the bows and bearing off in the lulls to get back on the correct course for the mark.

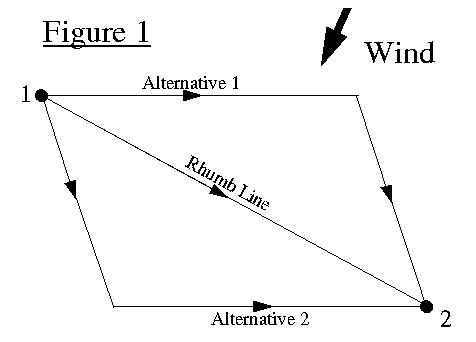

An extreme example of this occurs in really strong winds (top of F5+) and is illustrated in Figure 1. below:

On this particular reach, sailing along the rhumb line, even with the sail fully out, just causes the bows to dig in and a pitchpole is likely. Sailing either of the two alternative courses avoids the bows burying and allows negotiation of the reach in a more controlled manner.

Running

Prepare for the run by letting the sail out fully before you bear off around the mark. If it is not too windy it may be possible to release the downhaul without burying the bows, allowing the mast to rotate more fully. If this is not possible, forget about it and concentrate on sailing the boat, it is probably too windy for it to make a difference anyway.

Generally it pays to run lower in strong winds. This moves the force from the sail further forward (less sideways), spreading the 'burying force' between both bows reducing the tendency of the leeward bow to dig in. It is important to keep a careful eye on the burgee when sailing so low to avoid an involuntary gybe (with the inevitable consequences), I try and avoid the burgee pointing beyond the centreline during the gusts and generally sail with the burgee pointing between the windward rudder and the centreline in strong winds.

Gybing - Gybing can be achieved in a controlled manner in strong winds. The trick is to gybe through as small an angle as possible. Before the gybe bear off onto a dead run. Grab the mainsheet and start to pull it across whilst gradually bearing away further. As the sail comes across, straighten the rudders so that the boat ends up running on the opposite gybe. When ready point up to the desired course.

The best time to gybe is just after a big gust when the boat is still moving fast, this is when the force on the main is at a minimum.

Final Note

On a final note, the most important thing when sailing in strong winds is to know your limits. All of the techniques indicated in this article are best built up gradually through increasing wind strengths. If the wind is stronger than you feel confident to manage, don't go out. Wait until you have the opportunity to practice in slightly less wind and the confidence to sail in that stronger breeze will follow naturally.

Good Luck

George Carter

1818